Aftersun (Wells, 2022)

This might be an unconventional way to begin a review, but I cannot help but admire the gorgeous symmetry and simplicity of this title. The immediate reference is to aftersun lotions, like ones that contain aloe vera, which work to sooth and replenish tanned or sunburned skin. It is topical relief that, while not immediately healing a damaged skin barrier, still works to make its sting bearable. The title can also work more literally as shorthand for “after the sun.” Coming out of the light and into more shadowy terrain, leaving the warmth of the sun’s rays for something less certain and comforting, or even ending a sunny vacation and going back to one’s reality. The title encompasses so many meanings, both plain and symbolic, which ends up speaking to the many riches within Charlotte Wells’s debut feature.

Why, exactly, is it so rich? On the face it may seem a little humdrum, dealing as it does with an older woman remembering a childhood vacation in Turkey she had with her boyish father (so boyish, in fact, that they are mistaken for siblings). We all remember our family vacations: Tropical waters so warm to the touch, food dishes no one would ever make for us at home, exotic-looking souvenirs and trinkets, hotel beds of varying degrees of comfort, with strange insects buzzing over us on still or stormy nights. And always, always someone holding a camera or video recorder, snapping away to keep these memories permanent, pocketing film rolls and cassettes to put away in storage so they can be looked at years later. Wells highlights all these aspects here: First with a kind of nostalgic purity, and then gradually with an encroaching darkness that hints at something far more consequentially sadder than we’re first led to expect. For memories will change with time and circumstance. Things we were blind to in the moment can unfurl before us after years of distance, shocking us into submission at what we did not (or could not) see. One could even say the act of growing up is the recontextualization of all that we remember, and how newfound maturity can replace the solid colours of our naivety with the complex gradations of life’s darker truths.

This is why the title of this film is so perfect—why this film is so incredible and so wrenchingly intelligent. All of its pain bubbles quietly under its surface, slowly surfacing in the smallest revelations that continually measure out greater understanding of what has transpired from the very first frame. Wells imperceptibly moves us further and further from the sunlight of a child’s cheerful Turkish holiday—of arcade games with other tourist children and karaoke nights under the stars—to the twilight of a room several years later where these memories are being replayed on a TV screen. To the darkness, too, of a nightclub pulsing with strobe lights and dance music, where blurry shapes and bodies moving hectically in the din slowly come into sharper focus. The film becomes all about the gaze of painful hindsight and how loss can begin trickling into view much earlier than when its finality is realized. Both Paul Mescal and newcomer Frankie Corio are more than up to the task to bring Wells’s poetic meditations to fruition, and it’s their collective efforts that ensures the ending devastates us with the weight of its impact. Wells earns our emotional investment because she trusts us to read between each line every step of the way, and that kind of confidence will serve her extremely well in her nascent career as a cinematic artist.

Other People’s Children (Zlotowski, 2022)

The emotional trials of women of a certain age—particularly those wishing to be mothers later in life—are not always given the fairest shake on film, sometimes being depicted too glibly and lacking in sensitivity. Rebecca Zlotowski’s new film is something of a reparative in that respect, gracefully centering the newfound maternal instincts of a schoolteacher named Rachel (Virginie Efira) who, despite being around kids all the time, only begins to seriously contemplate offspring of her own when she starts dating a divorced man named Ali (Roschdy Zem) who lives with his four-year-old daughter Leïla (Callie Ferreira-Goncalves). Rachel showers Leïla with all the affections of a doting stepmother-in-waiting, picking her up from her judo class and buying her favourite snacks, but she cannot fend off also being the unmistakable “other woman,” as Ali’s ex-wife Alice (Chiara Mastroianni) remains in the picture—and also remains close in Leïla’s own heart. Zlotowski depicts Rachel’s burning need for a mothering outlet with both a sensuous lightness and an undercurrent of resignation, knowing that sharing other people’s children can be a difficult journey that yields as much heartbreak as it does happiness, especially when the children in question do not always want to be shared. And, even if they do, the adults in the picture need to be on the same page, too.

What works so well about this film is that it is generous in its candidness, while also ensuring that our connection to its protagonist is one guided by understanding and compassion. Efira’s performance clicks on the very first beat, exuding mountains of warmth as she flits through her Parisian life as the camera valiantly tries to keep up with her and Robin Coudert’s jazzy score twinkles brightly in the background. We see her at first as dizzyingly complete, with a touch of joie de vivre. Select comedic sequences further anchor us into her world, such as when Rachel memorably flees stark naked onto Ali’s veranda when Leïla seems about to barge right into an intimate moment between them, bearing out her impulsive soul for (literally) all the world to see. Zlotowski and Efira both deploy a bounty of good-naturedness right from the get-go, so that when Rachel’s role in Ali and Leïla’s lives gradually becomes more complicated and uncertain, the pathos that arrives provides a keen pang in our hearts as we see how some bonds cannot last as we would wish.

Other People’s Children, while not holding altogether surprising revelations about love and womanhood, also does not settle for the easiest ones, either. It recognizes that we must navigate our travails as they come, with the understanding that the wheel of fortune does not always spin in our favour. Rachel’s life, though depicted as deceptively easy and fulfilling at first, mellows out into a more sober and rueful trajectory as she begins to understand what she can and cannot change about either her body or her emotional outlets, and this ruefulness ends up making this venture so much more rewarding than you would first expect. By the time Rachel is caught in one final freeze frame, her face almost out of view as the frantic pace of life quickens once more, the weight of Zlotowski’s efforts careens into its fullest focus and we’re able to walk out feeling nourished.

De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Castaing-Taylor & Paravel, 2022)

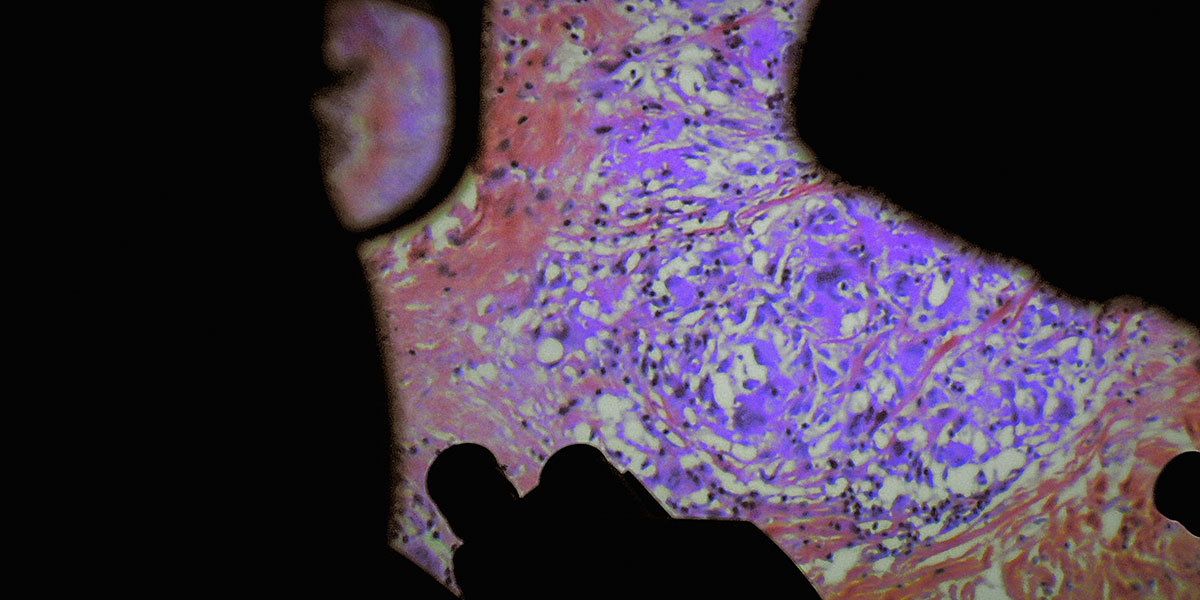

The filmic sensory ethnography of anthropologist duo Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel has yielded some of the startlingly upfront observational documentaries in recent memory. Screeching fishing trawlers (Leviathan), cannibalistic killers (Caniba) and imaginative sleep-talkers (Somniloquies) were plumbed with exacting rigour, and now they have transferred their lenses to perhaps their most universal subject yet: the human body. Filmed over a period of several years in various hospitals in France (Castaing-Taylor, during the screening’s Q&A, revealed that he and Paravel would travel to and from the different locations on bikes with all of their equipment), De Humani Corporis Fabrica is one of the most astonishing and unflinching glimpses into our corporeal realms ever filmed—certainly the most graphic and gripping depiction on record since Stan Brakhage filmed autopsy procedures for 1971’s The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes.

The major difference here is that, while we do see glimpses inside a morgue (and even nurses struggling to clothe a body in one grimly comical sequence), Castaing-Taylor and Paravel are almost entirely focused on living bodies being examined, probed, operated, scanned, repaired and, ultimately, saved from death’s maws. With a special miniature camera that could enter cavities and crevices rarely seen by the general public, the duo (with the consent of the hospital patients undergoing the treatments) introduce a kaleidoscopic, almost surrealistic montage of medical procedures that reorient our scope of the body’s beautiful and sublime strangeness. Yes, there are fluids and abject imagery that will not be for the faint of heart, but the duo’s intentions here are not really to disgust and revolt us. Rather, there is an effort to pierce into a sense of the miraculous: To show us the awe-inspiring resilience and ineffability of the cells, tissues and organs that make us the living, breathing beings that we are.

But there is also much more here working in tandem with all this sensational footage. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel also offer a rather pointed critique of a healthcare system in extremis, recording candid conversations amongst doctors and nurses overworked to the bone and struggling to meet the demands of their jobs. Even if many of these conversational snippets occurred years ago now, they nevertheless remain as prescient as ever, especially when healthcare systems remain in a state of crisis in places like Ontario, where the Toronto International Film Festival was held. I’m sure these conversations hit close to home for many members of my screening audience—it certainly did for me. But what truly makes this film so multifaceted is that the working environment in these hospitals is also examined with all its warts and deficiencies. At times, we are disturbed by how roughly a practitioner handles a patient or are shocked when we hear medical instruments being dropped on the floor. And certainly nothing can prepare a viewer for how the film ends, which reveals a truly bizarre tradition in hospital breakrooms involving orgiastic murals that certainly needs to be seen to be believed, much like everything else contained here.

Unsurprisingly, this is the most loaded film Castaing-Taylor and Paravel have made to date, even if it’s not as morally disturbing as something like Caniba. In fact, despite being replete with so much graphic imagery, it could very well be their most “accessible” thus far for all that it covers. Even if watching through squinted or covered eyes is sometimes a necessity, De Humani Corporis Fabrica already feels like one of the most vital and pioneering documentaries of the decade because of how thoroughly and unbelievably it lays everything on the line, providing us with a singular experience of unmatched perspicacity.

This Place (Nayani, 2022)

Lands both violent and peaceful yield crops of hope in V.T. Nayani’s feature debut, where Canada becomes the site of unconventional unions and forged ties without totally escaping its own colonial roots. It is this story’s nexus merely because faraway lands—namely Sri Lanka and Iran—are conflict-ridden and besieged by danger before Nayani’s story takes place in earnest, which has forced their sons and daughters to flee and raise their offspring in climates such as Canada that are devoid of obvious war and strife. And thus we have our two protagonists: Kawenniióhstha (Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs) is the daughter of a Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) mother and an Iranian father who left before she was born and thus still does not know of her existence, while Malai (Priya Guns) is of Tamil heritage, living with her older brother and reeling from the news that her alcoholic father is now dying of cancer in a local hospital. Both women meet by happenstance, unaware at first that they are living near-parallel realties driven by estranged patriarchal ties and loaded heritages they have yet to come to total grips with. But perhaps because of how cosmically aligned they are, they quickly fall in love and lend each other the clear realization that their respective unfinished businesses do, inevitably, need to be tended to. For closure, if not for comfort.

This Place is a film that at once revels in Canada’s cultural vibrancy—a place where migrants with fascinating histories raise their own equally fascinating children—while also being cognizant that its own damaged history relating to its Indigenous peoples is still very much an unhealed wound. We see this in Kawenniióhstha’s mother Wari, beautifully played by Brittany LeBorgne, who chooses to set her roots deep in the Kahnawà:ke reserve in Montreal during the Oka Crisis in 1990 rather than run from her people in their time of need—even if it means separating from the man she loves, and the father of her unborn child. In one emotional scene, Wari defends raising Kawenniióhstha as Mohawk in spite of her mixed race and tenuous blood quantum, laying out how much both her spiritual and emotional connection to Kahnawà:ke’s lands means to her and how not even the love of a man could get in the way of preserving that connection. The battle to preserve connections of all kinds becomes the shaping tenet of Nayani’s work, which is engrained in all facets of the film’s makeup, right down to showcasing the Mohawk place names for Toronto and Montreal, as well as preserving the heteroglossia of communication. Mohawk, Persian, Tamil and French are all uttered at least once (sometimes spontaneously in the middle of an English sentence), allowing viewers to see how fully and freely these characters live out their roots in the moment. Even when they are not thinking it, everyone in This Place is putting a piece of themselves in Canada’s vast fabric.

The film’s relative unsubtlety in expounding its priorities does weaken its impact somewhat. Nayani guides us very directly through its multiple conversations, crafting dialogue that becomes blunt in its ungainliness. Narratively, too, there is a tidiness that feels at odds with the characters’ inner conflicts, which feel more profound than the actual story that plays out before us. The romance between Kawenniióhstha and Malai, in particular, is not developed to its fullest extent, which robs some later scenes of stronger potency. But in terms of substance and the many issues it raises, This Place has quite a bit of merit, managing to overcome some of its imperfections by dint of striking a broader dialogue about our legacies and the lands on which we live them.